McDonald Bailey Jr

PIONEERS

‘Dad crossed the Atlantic to watch son in the Olympics’

Share this:

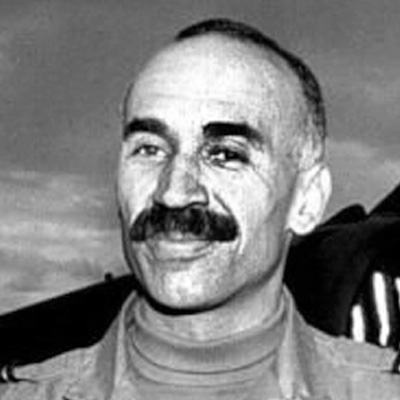

At age 67, retired Trinidad headteacher McDonald Bailey was one of the oldest passengers on the Empire Windrush.

Travelling alone in first class, he had boarded the ship in Port of Spain with the express intention of watching his son, Emmanuel McDonald Bailey, known as Mac, compete in the 1948 Olympic Games, which were due to start the following month on July 29.

These were the first Olympics to be held after the Second World War. Originally intended for Tokyo and then Helsinki, London had stepped in to host the event despite being ravaged by bombing.

On arrival, McDonald stayed with his son and young wife, Doris, at their home in Great James Street, Bloomsbury.

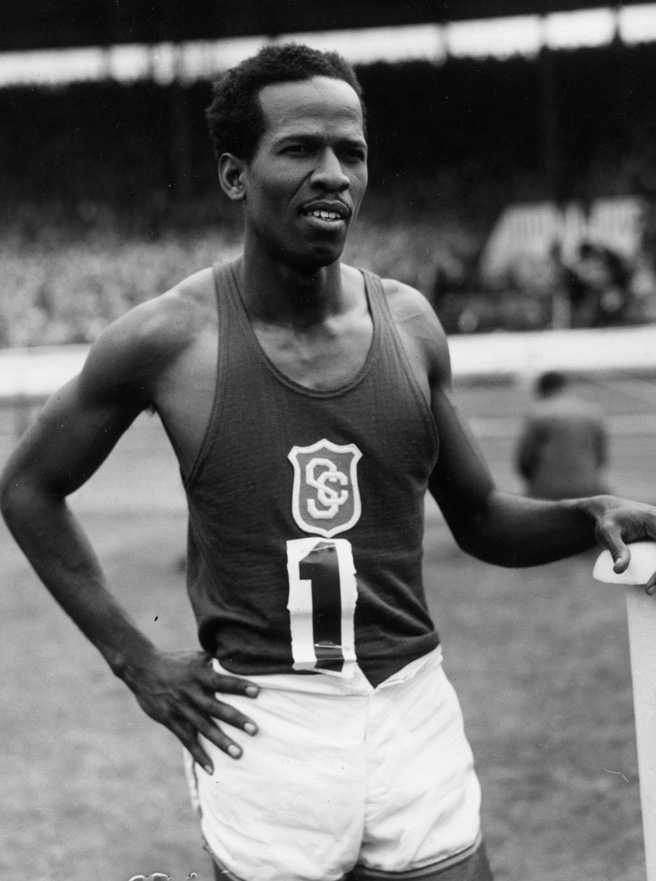

An outstanding sprinter, Mac was a real medal contender. But the run-up to the Olympics had been less than smooth for him. After being touted as one of Britain’s best hopes of a medal, the Olympic committee put the cat among the pigeons by inviting Mac’s native Trinidad to compete in the Games for the first time.

The rules in place indicated that Mac could represent Trinidad if he wished, and the Great Britain management team accepted this. However, Mac couldn’t make up his mind. As the Empire Windrush edged closer to England, McDonald had no idea whether he would be watching his son in the Great Britain or Trinidad vest.

When McDonald arrived at Tilbury, he found his son still riddled with doubt over which country to represent. Two other West Indian athletes, Arthur Wint and Leslie Laing of Jamaica, had been placed in a similar dilemma. They elected to compete for the country of their birth and Wint went on to win the 400m gold medal.

Previously, Mac and Wint had been Great Britain teammates. But in 1946 they had both been excluded from the European Championships in Oslo due to the fact that they were not ‘European born or naturalised’. This was despite the fact they held British passports and, more remarkably, were serving members of the RAF.

In the weeks before the Games, McDonald travelled around England watching his son in warm-up events and, as an ex-athlete himself, offering advice and support.

In mid-July, Mac finally decided to compete for Great Britain but, less than fully fit, he finished sixth and last in the 100m final. Four years later in Helsinki, he won bronze in the same event.

After he had seen his son compete, McDonald did not remain in the UK. He travelled to Liverpool where, on August 13, 1948, he boarded the SS Enid bound for his homeland.

Share this: